5. The Future is a Billionth of a Meter High

What could possibly lead us to a future beyond money? Our capitalistic free enterprise economic system is deeply entrenched in the Western developed nations and is being rapidly adopted by most other nations. Something massive would be required to change this paradigm. A world war, popular revolution, widespread and intense natural or manmade disaster, or a large enough technological breakthrough which could rewrite the rules.

Such significant technological breakthroughs may be considered as rare events, but closer examination reveals that the time between events is being shortened considerably. The quickening pace of change was pointed out by author Alvin Toffler first in his (now) classic Future Shock in the 1960s.[1]

In 1980 Toffler published The Third Wave which broadened the focus offering a sweeping view of past, present, and future. The main premise of his work is that we are caught up in the maelstrom of a third major cultural shift caused by technological changes, on par with two previous shifts, agriculture and industrial. Toffler’s vision however is not pessimistic, as he states in the introduction (referring to various recent crises):

Faced with all this, a massed chorus of Cassandras fills the air with doom-song. The proverbial man in the street says the world has “gone mad,” while the expert points to all the trends leading to catastrophe.

This book offers a sharply different view. It contends that the world has not swerved into lunacy, and that, in fact, beneath the clatter and jangle of seemingly senseless events there lies a startling and potentially hopeful pattern. This book is about that pattern and that hope.

[2]

The Third Wave is for those who think the human story, far from ending, has only just begun.

With the recent rise of an Internet economy, there is more interest in the accelerating pace of change as the following examples of recent books on the topic illustrate: Faster: The Acceleration of Just About Everything,[3] Instant Acceleration: Living in the Fast Lane, The Cultural Identity of Speed,[4] and Blur: The Speed of Change in the Connected Economy. [5]

The development of agriculture was a large enough breakthrough to change the social structure from tribal hunter-gatherer to highly organized city-states. The collective changes of the industrial revolution motivated a shift from rural agrarian to the highly urbanized cities where the majority of the population in western developed countries reside today.

Before each advance, most people were no doubt certain that things would stay the same, that they could project a straight line outwards from the present and predict the future. They were inevitably proven wrong.

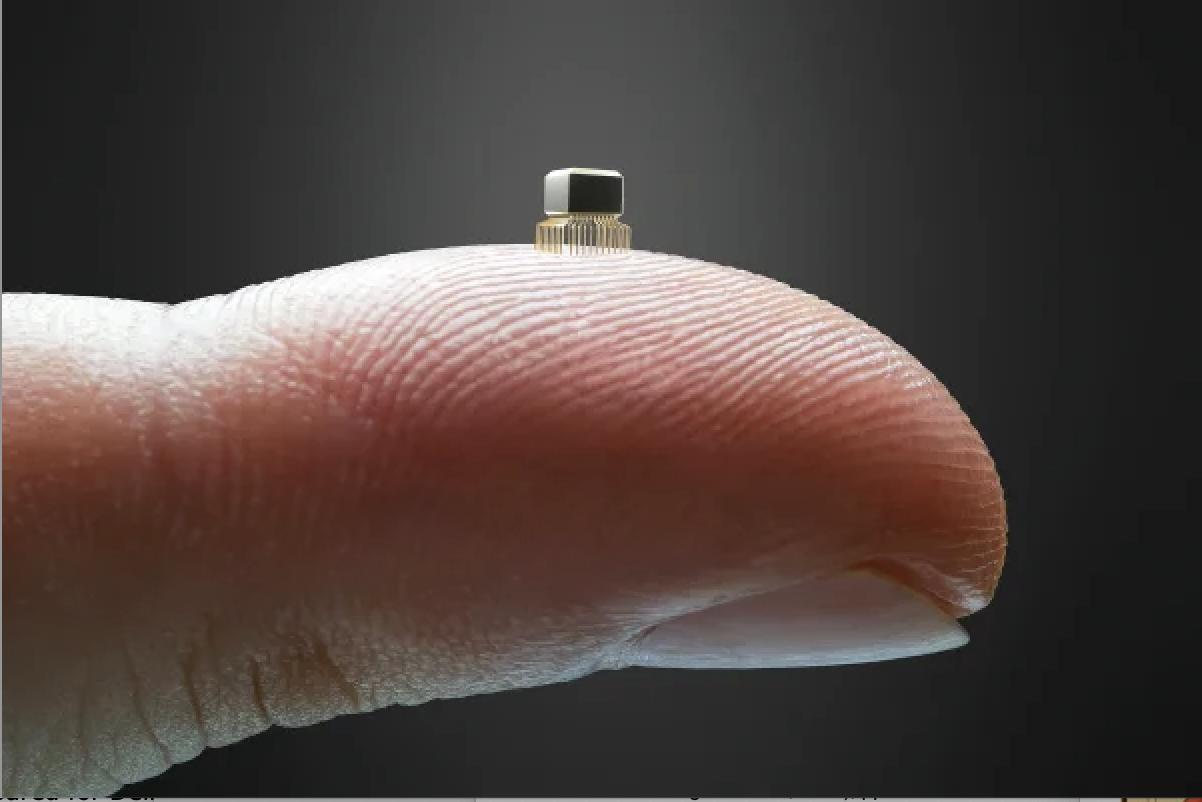

Now consider a near-future technology with significant enough implications for the future that it could perhaps lead to a fundamental social and economic shift – nanotechnology. K. Eric Drexler, widely credited as the “inventor” (or at least popularizer) of nanotechnology forecasts the manipulation of individual atoms and molecules by intelligent nano-scale (a nanometer is a billionth of a meter) robotic machines called assemblers, which will result in many astounding societal changes including those resulting from having manufactured products produced at costs approaching zero.

Nanotechnology is a human attempt to mimic the techniques nature uses when cells self-replicate, according to instructions encoded in the DNA which is located in the cell’s nucleus. “Machines able to grasp and position individual atoms will be able to build almost anything by bonding the right atoms together in the right patterns.” [6]

In the 1950s, nuclear energy was promoted as a future energy source that would be “too cheap to meter”.[7] It turned out to be an incredibly expensive boondoggle. In part, this was because utilities canceled 121 reactors in the post-1974 period; the money squandered on these canceled plants alone was about $44.4 billion in 1990 dollars.[8] Will nanotechnology be history repeated? Another empty unrealistic promise? Probably not. Nanotechnology is an extension of computer aided engineering, biochemical, and genetic engineering techniques that are already proven to be not only effective, but to reduce costs by order of magnitudes over the previous techniques they supplanted.

Drexler puts the net economic effect of this technology regarding manufacturing as follows:

Assemblers will be able to make virtually anything from common materials without labor, replacing smoking factories with systems as clean as forests. They will transform technology and the economy at their roots, opening up a new world of possibilities. They will indeed be engines of abundance.[9]

But what about limits, and past predictions of doom and gloom due to ecological crisis, overpopulation, toxic waste and pollution, and so on? Drexler addresses this paradigm as follows:

We need to prepare for the breakthroughs ahead, yet many futurists studiously pretend that no breakthroughs will occur. This school of thought is associated with The Limits of Growth, published as a report to The Club of Rome. Professor Mihajlo D. Mesarovic later co-authored Mankind at the Turning Point, published as the second report to The Club of Rome. Professor Mesarovic develops computer models like the one used in The Limits to Growth – each is a set of numbers and equations that purports to describe future changes in the world’s population, economy, and environment. In the spring of 1981, he visited MIT to address The Finite Earth: Worldviews for a Sustainable Future, the same seminar that featured Jeremy Rifkin’s Entropy. He described a model intended to give a rough description of the next century. When asked whether he or any of his colleagues had allowed for even one future breakthrough comparable to, say, the petroleum industry, aircraft, automobiles, electric power, or computer–perhaps self-replicating robotic systems or cheap space transportation?–he answered directly: “No.”

Such models of the future are obviously bankrupt. Yet some people seem willing – even eager – to believe that breakthroughs will suddenly cease, that a global technology race that has been gaining momentum for centuries will screech to a halt in the immediate future.[10]

Indicative of present day thinking on the economic impacts of nanotechnology is the subtitle of a recent book on the topic: Molecular Speculations on Global Abundance.[11] Essay contributors speculate on future applications and implications of this emerging science ranging from cosmetic nanosurgery to diamond teeth to board games with billions of moving parts. To say the least, surprising technological innovation is alive and well that will result in impossible to predict changes in our world.

Marvin Minsky, the artificial intelligence pioneer, had this to say about the future implications of nanotechnology and the difficulty of forecasting the future (in the Foreword to Drexler’s book):

For, as (Arthur C.) Clarke himself has emphasized, it is virtually impossible to predict the details of future technologies for more than perhaps half a century ahead. For one thing, it is virtually impossible to predict in detail which alternatives will become technically feasible over any longer period of time. Why? Simply because if one could see ahead that clearly, one could probably accomplish those things in much less time – given the will to do so. A second problem is that it is equally hard to guess the character of the social changes likely to intervene.

Now, if we return to Arthur C. Clarke’s problem of predicting more than 50 years ahead, we see that the topics Drexler treats make this seem almost moot. For once that atom-stacking starts, then “only fifty years” could bring more change than all that had come about since near-medieval times… nanotechnology could have more effect on our material existence than those last two great inventions in that domain – the replacement of sticks and stones by metals and cements, and the harnessing of electricity.[12]

Forecasts from the past can teach us an important lesson regarding those for the future. The next chapter provides a fascinating example.

[1] Alvin Toffler, Future Shock (Random House, 1970).

[2] Alvin Toffler, The Third Wave (New York: Bantam Books, 1980), p. 1.

[3] James Gleick, Faster: The Acceleration of Just About Everything (Pantheon Books,1999).

[4] Robert R. Sands, Instant Acceleration: Living in the Fast Lane, The Cultural Identity of Speed (University Press of America, 1994).

[5] Stan Davis and Christopher Meyer, Blur: The Speed of Change in the Connected Economy (Perseus Press, 1998).

[6] K. Eric Drexler, Engines of Creation (New York: Anchor Press / Doubleday, 1986), p. 58.

[7] “It is not too much to expect that our children will enjoy in their homes electrical energy too cheap to meter”, Lewis L. Strauss, Chairman, U.S. Atomic Energy Commission, “Remarks Prepared for Delivery at the Founders’ Day Dinner, National Association of Science Writers,” September 16, 1954.

[8] Charles Komanoff and Cora Roelofs, Fiscal Fission: The Economic Failure of Nuclear Power, A Greenpeace Report on the Historical Costs of Nuclear Power in the United States, prepared by Komanoff Energy Associates, Washington, D.C., December, 1992, p. 23.

[9] Drexler, Engines, p. 63.

[10] Ibid., p. 166.

[11] B.C. Crandall (Editor), Nanotechnology: Molecular Speculations on Global Abundance (Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press, 1995).

[12] Drexler, Engines, pp. v – vii.